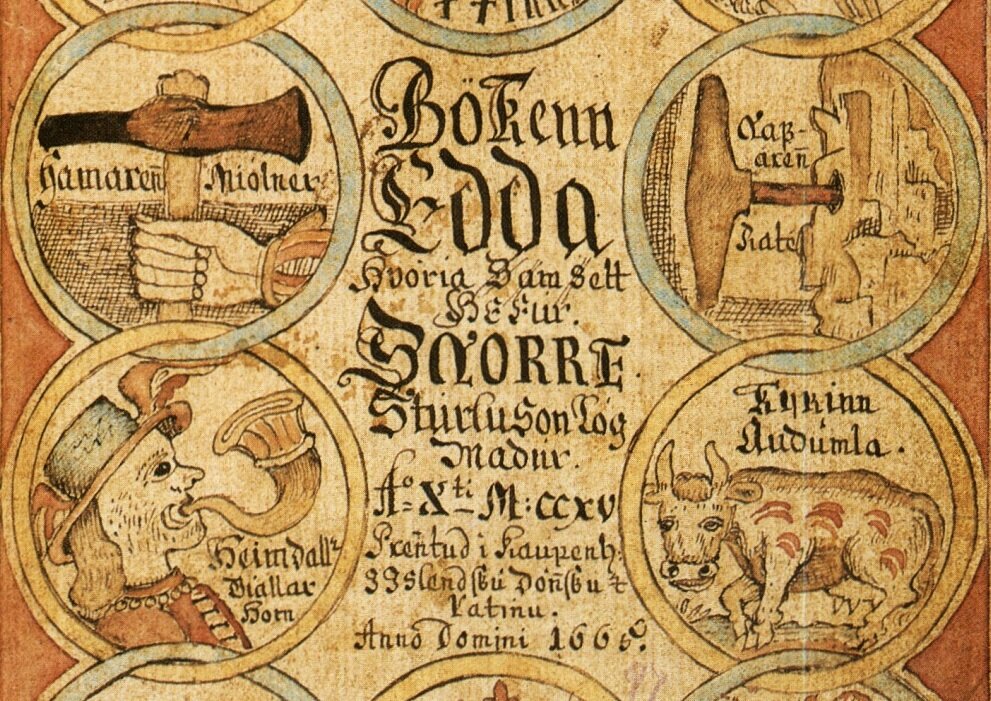

The Prose Edda is called Younger Edda, Snorri's Edda, or simply Edda. It was written in the 13th century and compiled by Snorri Sturluson, an Iceland Christian poet and law speaker. While the Prose Edda is hailed for its recounting old Norse mythologies from the world's creation down to Ragnarök, its intentions are more on how to write skaldic poetry rather than the preservation of Norse mythology.

The etymology of the word Edda isn’t entirely clear, but many believe it translates to ‘great-grandparent,’ while others think it is derived from the old Latin word ‘edo’, or ‘I write.’

Despite its original intent, it’s a fascinating look into the accounts of Nordic gods such as Thor, Loki, Odin, Freyr, and Ymir The Giant.

The Four Sections of the Prose Edda

1. Prologue

The prologue of the Prose Edda remains the most controversial of the four books. It was written by Snorri Sturluson, who was a Christian. The prologue of the Prose Edda reduces the Norse gods to fictional stories rather than theological accounts.

In the prologue, Norse gods are referred to as Roman Trojan warriors that fled Troy and settled in Northern Europe.

2. Gylfaginning

Of the four sections, the second section, or Gylfaginning, is ripe with Norse mythologies. If you want a rich account of Norse mythology, many read the Gylfaginning first. It depicts everything from the creation of the world to Ragnarök.

The title of this chapter comes from Gylfi, a king of Sweden, who travels to a palace in Asgard, where he encounters three men named High, Just-As-High, and Third.

During his encounter with the three men, he asks about the many Norse gods, as well as the creation and destruction of the world.

When the stories are complete, Gylfi has immediately transported away from the palace to his land, where he lives, telling the tales of what he encountered to his people.

3. Skáldskaparmál

As a text designed to teach the reader how to write skaldic poetry, the Skáldskaparmál dives deep into the poetry-writing process.

This third section is a conversation between Ægir, the divine personification of the sea, and Bragi, the god of poetry. It takes a deep dive into the Icelandic poet’s language and ways to recreate poetry in this manner properly.

While it’s a lesson in poetry writing, Ægir and Bragi sample from many quotes and passages from old Icelandic prose. It isn’t as rich in Norse theology as Gylfaginning, but essential texts are peppered through this section.

4. Háttatal

While other sections of the Prose Edda are samples of restored Norse poetry, the Háttatal is written entirely by Snorri Sturluson.

Overall, it uses the things learned through the previous section of this book to recreate Scandinavian-style prose.

If you want to learn more about Norse myths, Vikings, Æsir, and other Eddic poems, this section is not the place. It’s more of a lesson on verse forms and poetic diction rather than a historical account.

Prose Edda Vs. Poetic Edda

The Prose Edda is a sampling of some poems from the Poetic Edda. Overall, the Prose Edda is a much more manageable and easily digestible book compared to the Poetic Edda.

The Poetic Edda is a collection of 31 poems of unknown origin, and it can be challenging to follow for those not steeped in Norse mythology.

Snorri Sturluson’s edition of the Prose Edda organizes the poems that make it easier for the reader to follow and samples from only a few of the more important and influential poems depicting stories from Odin, Thor, and other old Norse tales.

Translations of the Prose Edda

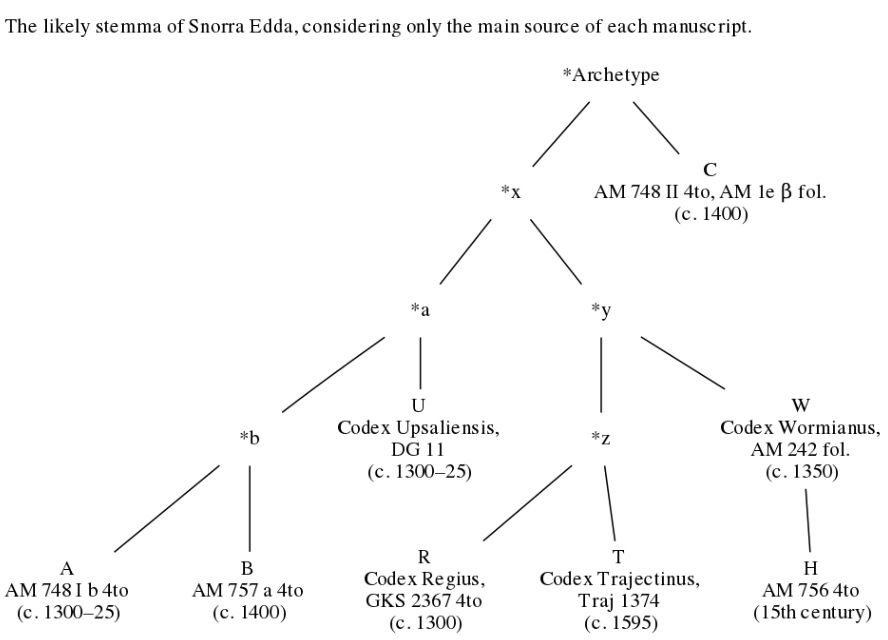

Not all English translations of the Prose Edda are created equal. In fact, there are six remaining manuscripts written between the 14th century to the 16th century, and they are all a little bit different.

While three remaining manuscripts are nothing but fragments of the original, four manuscripts remain entirely intact. They are called the Codex Regius, Codes Wormianus, Codes Trajectinus, and Codex Upsaliensis.

Of these four remaining manuscripts, the Codex Regius is the highest regarded. Compared to other remaining translations, the Regius is the most comprehensive.

When the Prose Edda is translated into English, it uses the Codex Regius as its template.

However, the Codex Upsaliensis, while not complete, contains some extra stories in the Gylfaginning that aren’t found in the Codex Regius.

About Prose Edda’s Author

To put it lightly, Snorri Sturluson wasn’t a very liked man. He was born in 1179 AD in Hvammr, Iceland. He was a notable chieftain, poet, and fierce historian, and the Prose Edda is one of the main sources of the preservation of Norse mythology. Snorri Sturluson lived until his ultimate assassination at his home in 1241 for betraying the king.

While his attribution to preserving the texts of North Germanic people and Norse mythology is essential, it wasn’t intentional. Sturluson’s Prose Edda is a collation from the Poetic Edda, which is the collection of 31 Norse poems of unknown origin and puts a Christian spin on classic Norse mythology.

In addition to the Prose Edda, Sturluson wrote other influential books, such as Heimskringla and the Viking Gods.

The Reason The Prose Edda is Sometimes Controversial

While rich in Norse mythology, the Prose Edda isn’t without controversy. Many reards have issues with this book because its author, Snorri Sturluson, was a Christian.

His intentions with the Prose Edda weren’t to preserve the records of the Norse gods (although he certainly did) but to create a scholarly text on writing Old Norse prose.

Despite its intention, the Prose Edda (especially the Gylfaginning) provides a great introduction to the origins and destruction of the Norse gods.